The January 1937 issue of Story magazine contained a short story about a New Year’s Eve party

thrown on December 31, 1930 in Vienna by an American journalist and his wife.

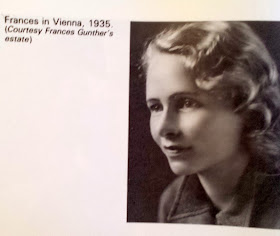

The twelve-page story, with the title “Another Year,” was written by Frances

Gunther, wife of journalist and author John Gunther. It is autobiographical, or

at least semi-autobiographical.

The lead characters in the story are Steve and his wife,

whose name we never learn, but who is telling the story from her

perspective (since she has no name, I refer to her as “Mrs. Steve). Aside from

Steve and Mrs. Steve, whom we recognize as John and Frances, many of the

story’s characters are identifiable as friends and colleagues of the Gunthers in

the Anglo-American journalist community living in Vienna in December 1930.

The story provides some insight into the lives of the people

in this group at this specific time and place.

It suggests the group had its libidinous elements. Apparently, the sexually charged atmosphere of

fin de siècle Vienna had survived, in some measure, World War I and the fall of

the Hapsburgs.

Also through this story, readers learn more about Frances

Gunther, who lived in the shadow of the man who was her husband from 1927 to

1944. Even more, the story provides another perspective of Frances and John’s

relationship, a subject prominent in the roman à clef, The Lost City, that John first wrote in 1937 and 1938, though it

was not published until 1964. The relationship had both its exciting and sad

elements, and the short story illustrates, in its own way, why.

The Short Story: “Another

Year”

The short story can be summarized as follows:

Plans for a New Year’s Eve Party

The story begins with Steve and his wife talking to Clive Dennis

and Kate Pond. The first two had

recently arrived in Vienna, where he was a foreign correspondent for an

American newspaper. Clive and Kate, also

American journalists, had been there for a few months. The four were discussing different members of

the foreign journalist community in Vienna when Clive complained about the tame

New Year’s Eve party given the previous year by the Schnabels. He asked, “What

the hell kind of party is this: No drinking, no smoking, no kissing?”

Steve offered to hold the next New Year’s Eve party at the

large apartment he and his wife have rented. He said, “We’ll show ‘em what a

New Year’s Eve party is, won’t we kid?” His wife replied, “Sure, we’ll show ‘em.”

The Party Begins

Sixty people showed up for the party. The centerpiece was a

pig: “There was a great pig’s head in the middle, surrounded by lots of little

pig’s heads and roast ribs of pork and, of course, hams.” The punch was as “smooth as nothing on the

tongue, but with a lift like a skyrocket.”

At midnight, with the house lights off, people waved

sparklers and shouted “PROSIT NEUJAHR,” clicked glasses and ate Lebkuchen and

pigs head, especially the nose, “which is extra good luck, especially if you

keep it in your purse all year.”

Until three, the party was a huge buzzing crowd. As Steve’s wife described it, “It was all

crowd, crowd noise, crowd smell, crowd feel. A babel of crowd.” She liked this:

it was too loud for people to spill their souls, to make connections, to tell

their stories. All that could be said was things such as “Hello—everything’s

swell—have a drink—swell--drink.”

The Party Dramas

The crowd at the party started thinning after three a.m. and

the small dramas began heating up. These dramas stemmed largely from the

relationships different people brought to the party. Much of the dramas had to

do with sex.

Lee

Pugh, Mrs. Foster, and Miss Libby

At the center of one small drama was Lee Pugh, described by

Mrs. Steve as “one of our best friends, who covered for a half a dozen papers

under various names.” When the party was being planned, he had told Steve that

he wished that Mrs. Foster would not be invited to the party. Apparently, she

often joined the journalists at their café, and Pugh thought she was pursuing

him. He told Steve, “That woman’s a nymphomaniac, that’s what she is – the way

she goes after a guy – je-sus!”

Kate, on the other hand, wanted her invited. She told Mrs.

Steve that Mrs. Foster, a psychology professor at a woman’s college on a study

leave in Vienna, is “a splendid woman.” Kate said, “Pugh makes me sick. Every

time a woman looks past him to look at a clock, he thinks she is trying to get

her claws into him. Just because the Countess hangs onto him like a bug on

flypaper, he thinks every other woman is crazy about him too. He makes me

sick.” Mrs. Steve remarked elsewhere,

“Every woman who wants to get beaten up is attracted to Pugh.”

The party hosts invited Mrs. Foster to the party as well as

Miss Libby, a young woman who was crazy about Pugh. Though he actively disliked

Mrs. Foster, Pugh just ignored young Miss Libby.

Mason,

Franzi, Mr. Daggett, and Miss Libby

Another small drama in the short story involves a character

named Mason, who has just returned from a reporting trip to India, and his

“girl,” Franzi. According to Mrs. Steve,

“Franzi was young. She was no great beauty. But she was all young, her eyes were

young, her breasts were young, her thighs were young.”

Mason and Franzi were enthralled by each other and obviously

in love. However, Franzi had been the secretary of Mr. Daggett, another

journalist who “is the author of a half dozen standard works on European

politics.” Mrs. Steve had learned from Steve that Daggett had either had

something going with Franzi, or had wanted to. He is at the party with his

wife, whom he evidently detests.

As Mason and Franzi danced and reveled in their mutual

attraction, Daggett watched Franzi, his eyes “glued to her thighs.” His wife watched

him watch Franzi and suggested that it was time to go home. He replied to her

angrily. Mrs. Steve noted, “You could see him hating her because Mason had

taken Franzi from him—as if it were her fault.”

Mason was upset at Daggett for staring at Fritzi. She was embarrassed.

The two lovers soon slipped away from the party.

About this time, Miss Libby was leaning against the bar. According to Mrs. Steve, “she was very tall

and wore a long dark dress opening down the front to about her belly button.”

Miss Libby had talked to everyone at the party, except Pugh,

“who was the only one she wanted.” Mrs. Steve observed, “No matter whom she

talked to, she kept looking around to Pugh, as if she were a sunflower and he

the sun.” Daggett came over to her and after

some inebriated chatting, they both disappeared from the room. His wife -- “handsomely gowned” with “fine

intelligent blue eyes”, but “heavily made up and henna-ed” -- pretended she

didn’t notice.

Steve’s

“Little Russian Dancer” and Tony

The third small drama concerns Steve’s “little Russian

dancer.” His wife had suggested she be invited to the party. Steve said that he

thought she would be out of town. Mrs.

Steve said, “Why not call her up to find out.” He said, “Oh you call her up.”

She said “Yes, and then I suppose you’ll want me to put her in bed with you and

tuck you both in.” Steve said, “You have the brightest ideas darling.” When invited to the party, the dancer agreed

to come as long as she could bring along a female friend.

In an early morning hour, Mrs. Steve observed Steve “playing

with the little Russian dancer.” According to her, “She wore a bright red dress

and she was even younger than Franzi, though she looked older and not so pure.”

When Steve asked, the little Russian dancer told him she was seventeen.

About that time, Mrs. Steve danced with Tony, “a beautiful

boy who writes music or something.” He subtly solicited her interest, but she

refused to show any, though if she were seventeen, she thought, she was sure

she would.

Then the Party Ends

As the hour nears 6 a.m. the party begins to wind down. Steve spots three gatecrashers who have

arrived and cheerfully introduces them to everyone. Mrs. Foster, with her “gold

hair, black gown, bare back and diamante,” says, “Three men. Did I hear that

three new men had arrived?” Not long after, she disappeared from the party with

them, never to return. Steve remarked, “Pretty swell course in psychology that must

be.”

Daggett and Miss Lilly return and, Mrs. Steve observed that

“the miracle of the flesh has performed its beneficent wonder. Daggett’s face was still red, but the hate had

gone out of his eyes, he was just drowsy and peaceful.” He and his wife soon

left the party.

Thinking about how Steve had so much enjoyed the little

Russian dancer, Mr. Steve considers asking Steve to take her home and she would

“keep Tony here.” Then, she thought,

“You’re a fool, it’s another year – still another new year – one more again –

and you can’t go back to that sort of thing.”

Pugh started to leave. Libby followed closely behind. She

asks if she can go with him. He says, “Sure, suit yourself.”

Then, it was after six a.m., only Mr. and Mrs. Steve, Clive,

and Kate were left. They played some ping pong, then Clive and Kate crashed at

the apartment.

Steve and his wife were alone in their bedroom where they

opened a window to eat fresh snow. He says, “You know, I nearly took the little

Russian girl home.” She asks why he did not. He says, “I wanted to stay with

you more.” “That’s nice.”

With fresh pajamas, they snuggled in bed. He says, “It’s

been a great party, Happy New Year.” She replied, “Happy New Year darling.” The

story ends with this remark: “we saw that it was pretty good after all and we

fell asleep.”

Behind the Story of

the 1930 New Year’s Eve Party

Frances Gunther’s short story is based, at least in part, on

the New Year’s Eve party that she and her husband threw on December 31, 1930.

We know something about this party because Martha Foley, who was there, wrote

about it:

The Fodors, the Gunthers, and we

combined forces and funds to give a New Year’s Eve party for the

correspondents’ group. We held it on the spacious second floor of the Gunther’s

rented mansion, where there was plenty of room for dancing. Newspaper people

have a gift for the convivial, and I have never known them to give a party that

was not a success. Ours was no exception. There was an abundance of good food,

good drink, and good talk.

A roast suckling pig was the pièce de résistance on the buffet table. In the Viennese tradition, each guest was served a tiny piece of its ear, with the admonition to carry it at all times. Like a rabbit’s foot in America. It would bring us something we were all going to need desperately – luck. Never again for many years would there be such carefree New Year’s festivities as on that eve of 1931 – not in Vienna, not anywhere in the civilized world. (The Story of Story Magazine, pp 125-126)

As discussed below in more detail, Foley and her partner Whit

Burnett are characters in the short story.

Steve, Mrs. Steve, Clive, and Kate, plus the Schnabels

In the short story, as previously noted, Steve and his wife are

John Gunther (1901 – 1970) and Frances Fineman Gunther (1897 – 1963) who moved to

Vienna in June 1930. He had been appointed by the Chicago Daily News to head its bureau there. The two had married in

1927, and when they were not traveling around Europe for the newspaper, they had

lived in Paris. Shortly before moving to Vienna, they had had a son, whom they named

Johnny.

Clive Dennis and Kate Pond are Whit Burnett (1900-1972) and

Martha Foley (1897-1977), who had also moved to Vienna from Paris, arriving

some months before the Gunthers. Burnett was a journalist with the New York Sun; she was also a

journalist, sometimes writing for the Consolidated Press news syndicate and other

times doing freelance work. Though they lived together in Vienna, they did not

marry until later.

While in Vienna, the two started publication of Story magazine (in which this short

story was published) as a literary outlet for short stories. The first issue,

dated April/May 1931, was reproduced on a mimeograph machine located in a room

for journalists (Journalistenzimmer) in the Vienna Central Telegraph Office. They left Vienna in 1933 when their jobs

disappeared. They and their magazine

moved to New York City. By the late 1930s, its circulation had reached 21,000. The

magazine was published on-and-off until 2000. [See the “Story Magazine”

entry on Wikipedia]

The Gunthers were good friends of Burnett and Foley, even

after they all had left Vienna. However, Foley did not like John very much. She

claimed that he “detested women journalists” and that he had run around on his

wife in Paris when she was in the hospital to give birth to their son. She

wrote:

We became such close, lifelong

friends with the Gunthers that we seemed at times almost like one family.

Whenever we were in the same country we celebrated Thanksgivings and

Christmases together. Their son, Johnny, often stayed with us when they took

trips, and our problems, professional or domestic, we discussed in common. But

it was never really a four-way friendship. The relationship developed because

Whit and John liked each other, as did Frances and myself. (The Story of Story Magazine, p. 125)

The identity of the Schnabels, who threw a boring party in

1929, is uncertain. The story indicates

that they were natives – meaning they were from Vienna, elsewhere in Austria,

or Central Europe. Among the possibilities are (1) Friedrich Scheu (1905 – ????),

a young Viennese lawyer, who also was the correspondent for a left-leaning

newspaper in Britain, (2) M.W. Fodor (1890 – 1977) and his wife Martha (1900 –

1959; he was born and raised in Budapest, she was born in Slovakia; he had been

the correspondent for the Manchester

Guardian since 1919 and had also started reporting for the Philadelphia Public Ledger in 1927; and

(3) Emil Vadnay (1885? – 1939), a Hungarian employed by the New York Times.

None of these people could be suspected of throwing a dull

party. Scheu was the son of a prominent lawyer, and his mother was Helene

Scheu-Riesz (1880-1970), a famous writer of children’s books who kept a popular

salon in Vienna at the time. Fodor was

the son of a Hungarian industrialist who had grown up with the finer things.

Vadnay had been an officer in the Hungarian army during World War I who had

become a journalist. He was known for his winning personality. According to his

college G.E.R. Gedye, Vadnay “was immensely popular” with his peers and “a

generous host.” [New York Times,

April 2, 1939, p. 62]

Another possibility is Alfred Tyrnauer (1897 – 1979), correspondent

for the International New Service. Tyrnauer was born in Kassa and had a

doctorate in economics. He had reported from Vienna beginning in 1927, but

worked for a news service that did not pay good salaries.

The Unlikable Lee Pugh

In this short story, the character of Lee Pugh is clearly

Robert Best (1896-1952), who was a correspondent in Vienna for the United Press

news bureau. Best was a central figure in the Anglo-American journalist

community from the middle 1920s until 1940. He had established and presided

over the most popular meeting place for Anglo-American journalists in Vienna, the

Café Louvre.

Best had arrived in Vienna in December 1922 and found a job

with the United Press news service. This job paid poorly, and he supplemented

his income by assisting journalists when they were working away from Vienna or

were on vacation. He also set up a small press agency for journalists in

Vienna.

|

| Press Photograph of Robert Best (left) with his sister and brother, receiving a birthday present on his 52nd birthday; on that day, he was convicted of treason |

Best’s colleagues liked him, even though he was considered

peculiar. Among the strangest things about him was his relationship with a

mysterious older woman who was a “countess.” She and Best had a strange and

stormy relationship that mortified his friends. The two are major characters in

Gunther’s The Lost City (Best’s name

in the book was Jim Drew). Also, they

are the basis for the lead characters in The Traitor,

a book written by William Shirer after World War II. The title refers to Best, who

remained in Austria after the Anschluss and refused to leave Germany after the United

States declared war on that country. During the war, Best worked as a radio

propagandist for Germany, with his anti-Semitic diatribes transmitted to the

U.S. from Germany. After World War II, he was convicted of treason by a U.S.

court.

Mason and Franzi in Love

In the story, the character named Mason is clearly William

Shirer (1904-1993), who was the Chicago

Tribute correspondent in Vienna from 1929 to 1932. Franzi is Theresa (Tess)

Stiberitz (1910 - 2008), a Vienna native. During 1930, Shirer spent many months

in India and had returned near the end of the year to Vienna. He and Tess were

married on January 31, 1931, a month after this party was held. As Shirer

described in The Nightmare Years, volume

2 of his autobiography, the wedding was a civil ceremony at the Vienna City

Hall. The only witnesses were their

friends Emil Vadnay and Emil’s Viennese wife.

According to the biography of John Gunther, he (John) formed a

close friendship with Tess when they were both in Vienna, and often confided in

her. Perhaps this relationship contributed to Frances' assessment of her in the

short story as “no great beauty.”

The Daggetts, the Little Russian Dancer,

and Tony

The least sympathetic person in the short story is Mr.

Daggett. The real identity of this character is unknown, and it is not known if

Tess, soon to marry Shirer, had worked for him.

None of the foreign correspondents in Vienna in 1930 was the “author of

a half dozen standard works on European politics” – which in the short story is

Daggett’s main identifying characteristic.

Perhaps the identity of this character was obscured to avoid overt

insult or libel.

(It should be noted that all of the people who were

characters in this short story were still alive when it was published, and many

of them were still John Gunther’s friends and colleagues. Some of them likely

were not pleased with how their characters were portrayed.)

The identity of the little Russian dancer is also not

known. From his biography and the semi-biographical

book John Gunther wrote, it is known that he was a social and fun-loving person

who liked to attend cabarets in Vienna and became acquainted with many young women

there. Specifically, it is documented that while in Vienna, John Gunther fell

for a young actress, Luise Rainer (1910 -

) before she went to Hollywood,

where she won academy awards as best actress in 1935 and 1936. (As of January

2014, she is still alive, living in England). According to Shirer, quoted in

Guther’s biography his interest in Rainer was a source of tension with Frances.

The identity of Tony is not known. Apparently, during the

last years of her stay in Vienna, Frances was well acquainted with many Tonys

whose attention she did not reject.

The Gunthers and Life

in Vienna After the 1930 New Year’s Eve Party

The short story ends on a tenuous, but hopeful note: “It was

pretty good after all and we fell asleep.” However, by the time readers get to

the end of the story, they realize something is off kilter. The story is a

modest, understated tale that shows a keen eye for people and their behavior.

It makes no judgments and shows no overt cynicism or emotion about what is

happening, even when they seem justified.

Mrs. Steve – that is, Frances – is calm and apparently complaisant

when contemplating her husband’s interest in the teenaged Russian dancer. And she

has no particular anxiety about her subtle encounter with Tony and its

possibilities. The essence of her state of mind and the situation is evident

when she calmly thinks about sending Steve to take the dancer home while she

would “keep Tony here.” She rejects the idea: “It is another year” and “you

can’t go back to that sort of thing.”

This one phrase “you can’t go back to that sort of thing”

tells its own story and provides the context for understanding where Frances

and John were in their relationship. It was a difficult one and would get worse.

Gunther’s biographer attributes most of the difficulties to

Frances, who suffered abuse as a child. According to his account, she tricked

John into marrying her by telling him – when she was in the U.S. and he was in

Europe – that she was pregnant. When she showed up for the wedding, she was

not. The decision to marry her was one “John would regret for the rest of his

life.” (Cuthbertson, p. 73) He told

Shirer in the 1930’s, “You don’t know the hell I am living through.” (Cuthbertson,

p. 113)

Gunther’s biography describes Frances as “a very disturbed,

angry woman” who was “moody and unpredictable” (Cuthbertson, pp 113, 115). In

the last year or so in Vienna, she had a “series of sad affairs.” (Cuthbertson,

p. 115)

Frances did not have a biographer to explain her actions or

delve into her husband’s, but some of her friends, including Martha Foley,

thought highly of her. She wrote, “Frances, on first meeting people, studied them with the candid,

questioning gaze of a child, and she was considered cold. Appearances were

deceiving.”

Another friend, Friedrich Scheu, the Viennese

lawyer-journalist who worked with her and John during their time in Vienna,

wrote the following about her:

…in her Vienna years [Frances]

looked like a delicate blond doll, like a gentle kitten. In reality she was a

lightening quick woman with open eyes and a very sharp tongue….It was almost

accepted that during the years of John Gunther’s rise, she was the driving,

dynamic force behind his efforts. She could also write – after 1934 she worked

for a while as the Vienna correspondent of the “News Chronicle.” She was an amusing

and intelligent colleague. I once saw one of her written “Novella,” that

circulated in manuscript form. In it she described her colleagues in a humorous

but blunt way.” (Scheu, p. 61; my translation)

Whatever, Frances’ strengths or weakness, living with John

Gunther could not have been easy. He had many admirable traits, including great

charm, admirable generosity and strong loyalty to friends. He was in many ways

larger than life: ambitious, hardworking, high living. However, in The Lost City, the character of Mason

Jarrett -- John Gunther as he saw himself -- is a humorless, tedious womanizer

who has such a grand view of himself that he could justify anything he did and

excuse himself for his transgressions.

Among his many transgressions was an effort that began in

1939 to persuade Agnes Knickerbocker, the wife of a good friend and fellow

journalist, H.R. (Red) Knickerbocker, to leave her husband to marry him. This

effort came at a time he was still married to Frances. (Cuthbertson, p. 190)

Whatever Frances problems and however her husband

contributed to them, she was obviously well educated (she graduated from

Bernard College) and intelligent. She had ambitions to be writer, but little of

her work was published. Her most ambitious project, an analysis and history of

Empires which she worked on for twenty year, was never completed.

Frances’ and John’s marriage survived the Vienna years and

the years of his first success with the “Inside” books. However, the couple

finally found it impossible to live together. They divorced in 1944, though

they had separated emotionally by the beginning of the decade.

Sources Consulted

Burnett, Whit. 1939. The

Literary Life and the Hell with It. Harpers and Brothers.

Cuthbertson, Ken. 1992. Inside:

The Biography of John Gunther. Bonus Books.

Edwards John Carver. 1982. Bob Best Considered: An

Expatriate’s Long Road to Treason,” North

Dakota Quarterly 50(1), Winter, pp. 73-90.

Foley, Martha and Jay Neugeboren. 1980. The Story of Story Magazine, W.W. Norton.

Gedye, G.E.R. 1939. Literature His Hobby. New York Times, April 2, p. 62.

Gunther, Frances. 1937. Another Year. Story, vol. X, no. 54, January, pp. 74-85.

Gunther, John. 1964. The

Lost City. Harper & Row.

Scheu, Friederick. 1972. Der Weg ins Ungewisse. Verlag

Fritz Molden.

Shirer, William. 1950. The

Traitor. Farrar Straus

Shirer, William. 1984. The Nightmare Years, vol. 2 of “20th Century Journey.”

Little, Brown, and Co.

After reading the biography of John Gunther, I believe that Frances was bipolar.

ReplyDeleteShe may have been. Obviously a troubled woman. Of course, John Gunther didn't help; he was a narcissistic womanizer, but also, from all evidence a genuinely good friend and effusive personality. Reading the Lost City, which features John and Frances as the leading characters, it seems clear they did not do well together and neither was blameless for that situation.

Delete